Download PDF

Fertilizer Costs on the Rise

Surging agriculture input costs, especially the prices of fertilizer and fuel, have been top of mind for many Canadian farmers as they kick off the 2022 seeding season. Fertilizer prices reached multi-year highs in Q4 2021, and the emergent conflict in Ukraine in early 2022 has only exacerbated the already-strong upward pressure on market prices.

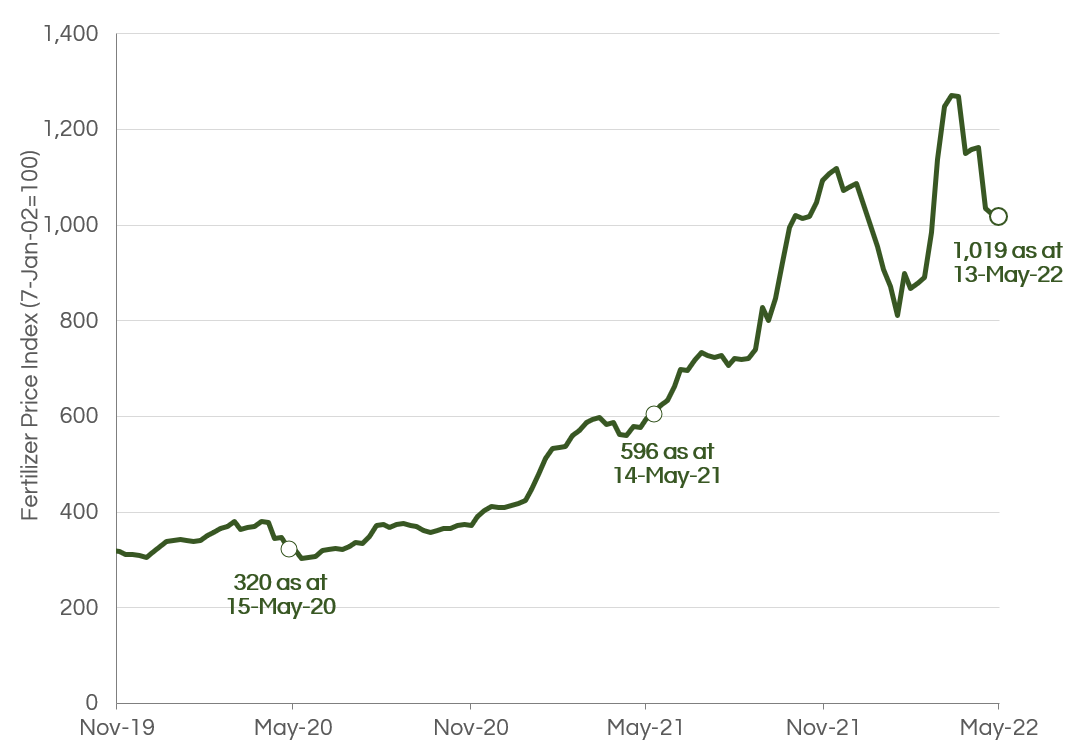

According to Bloomberg’s Green Markets Fertilizer Price Index – which tracks North American fertilizer prices over time – fertilizer prices have more than tripled since early 2020.(1)

Green Markets Fertilizer Price Index (Nov. 2019-May 2022)

Source: Green Markets, a Bloomberg LP Company

The global supply chain has been massively disrupted since the onset of the global COVID-19 pandemic, as logistical bottlenecks built up at the world’s largest shipping ports while nations experienced labour shortages due to lockdowns, and dislocations affected shipping routes, air cargo, ground transport lines, and railways(2).

As countries around the world began to loosen pandemic-related restrictions through late 2021 and 2022, commodity prices have soared as result of pent-up demand and supply constraints, with fuel prices rising significantly. In addition, several recent events have further restricted the supply of fertilizer chemicals, such as ammonium phosphates, nitrogen, potash, and urea, resulting in continued upward pressure on prices:

- Extreme Weather in the U.S.: Hurricane Ida hit the U.S. Gulf Coast in September 2021, effectively shutting down production and causing serious shipping delays and logistical challenges in New Orleans – the U.S.’s main trading hub for fertilizers(3);

- Chinese Export Policy: China, one of the world’s key suppliers of urea, sulphate, and phosphate, imposed new customs regulations in October 2021 that included enhanced inspection requirements and new export certificates on a wide variety of export products, including urea and ammonium nitrate, that effectively curbed the export of fertilizers from the country. This move followed a September 2021 circular from China’s National Development and Reform Commission, the country’s economic planning body, calling for stability in fertilizer prices in the domestic market(4);

- Russian Trade Restrictions: Russia temporarily halted the export of fertilizers from the country in March 2022, citing a lack of logistical connectivity and lack of transport ship arrivals in Russian ports after commencing an attack on Ukraine that continues to occur as at time of writing. Notably, Russia is also a major producer of potash, phosphate, and nitrogen-based fertilizers, and many countries have implemented sanctions against Russia as well as tariffs on Russian goods(5).

Fertilizer exports from the U.S., China, and Russia have historically reached differing end markets, with the main destinations for U.S. fertilizers being Canada, Brazil, and Mexico, whereas some of the key markets for Chinese and Russian fertilizers include Brazil, India, Australia, and Estonia(6). That said, the developments highlighted above collectively have led to an unprecedented strain on the global supply of fertilizer chemicals, thus impacting farmers and food prices across the world.

Global Fertilizer Trade

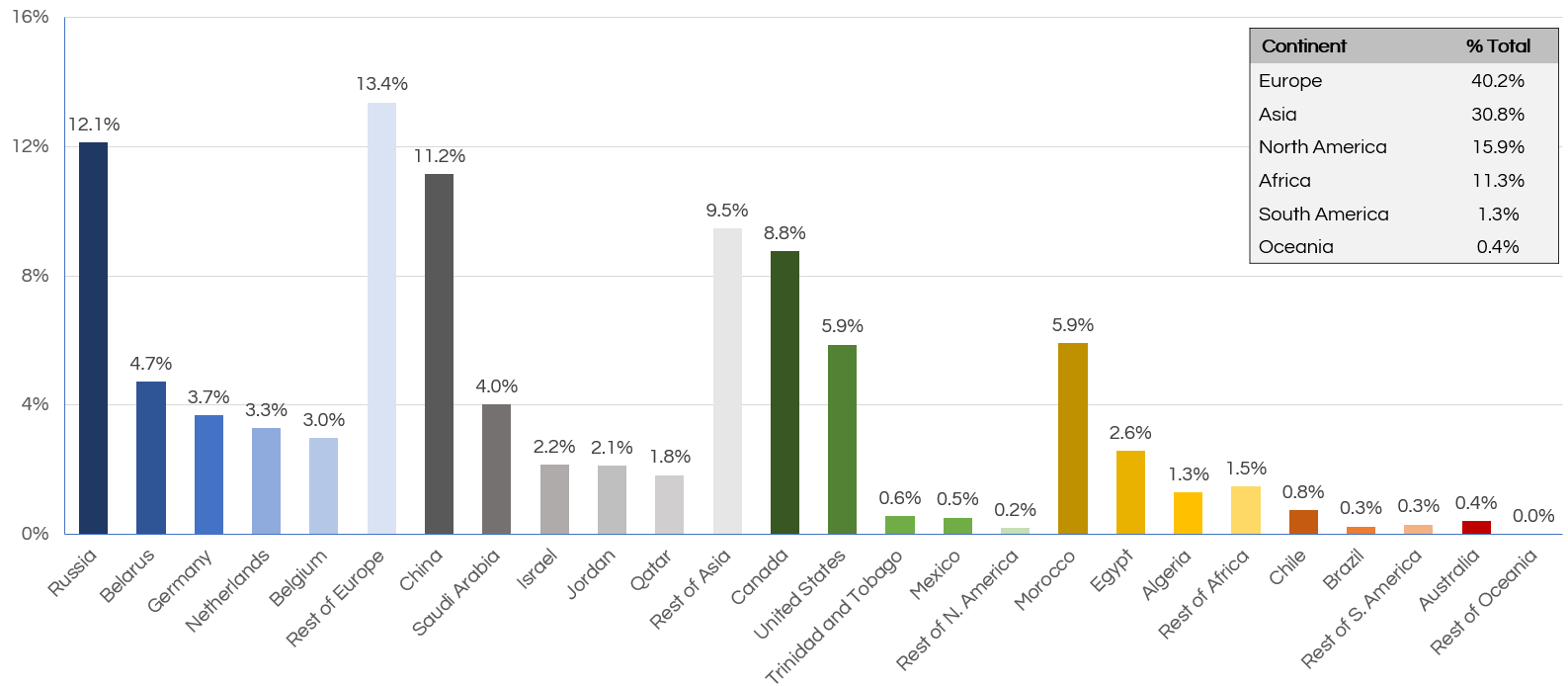

Fertilizers represent one of the world’s most heavily traded product types and, as shown below, the largest exporters in 2020 were Russia, China, and Canada

Largest Global Exporters of Fertilizers – Share of Global Export Trade Value by Country (2020)

Source: Observatory of Economic Complexity.

As noted, Russia and China have recently implemented increasingly isolationist-style export policies and, in 2020, the two countries accounted for ~23% of fertilizer exports globally(6). With these two major exporters limiting outbound trade of fertilizers, as well as the war in Ukraine and its trade implications (e.g., sanctions affecting the ability import of Russian goods), countries around the globe have directly felt the impact of supply limitations. Brazil and India stand to bear the brunt of the immediate supply shock, with Brazil and India having sourced ~26% and ~31% of their fertilizer imports from Russia and China collectively(6).

In Brazil’s case, there are concerns that the uncertainty and extremely elevated costs associated with sourcing fertilizer could hinder crop yields, resulting in a smaller harvest and even higher global food prices higher given the country’s importance in global crop markets. This is in addition to existing concerns around Brazil’s 2022 yields due to the possibility of extreme weather, like the severe drought experienced during the 2021 growing season(7). Brazilian farmers are considering various strategies of dealing with the shortage; SLC Agricola SA, one of the country’s largest producers of soybeans, corn, and cotton, is planning to reduce fertilizer usage by up to 25% in the coming year(8). On the supply side, major fertilizer producers are exploring ways to ramp up production, but doing so will take time and is thus not an immediate possibility. Canada’s largest potash producer, Nutrien, has committed to increasing its potash production by almost 1 million tonnes this year – the ramped-up production is expected in the second half of 2022(9), which is after the Northern Hemisphere’s seeding season. In summary, while major food and chemical producers alike are employing their best efforts to stabilize prices and ensure continuity of supply for both fertilizers and food, it could take months (or longer) before the impact of those efforts is seen.

A Canadian Perspective

Canada is the world’s third-largest exporter of fertilizers and has historically imported significantly less fertilizer in aggregate than it has exported(6). In 2020, the total trade value of fertilizers exported from Canada totalled approximately US$5.5 billion (C$7 billion(10)), whereas the total trade value of imported fertilizers was approximately US$1.4 billion (C$1.8 billion(10))(6). Notably, Canada is the largest global producer and exporter of potash, which refers to a group of chemicals and minerals that contain potassium (such as potassium chloride) that are most commonly used in fertilizers(11). Canada exported 22 million tonnes (“MT”) of potash in 2020, accounting for approximately 39% of the world’s total exports(11).

From this perspective, it may seem that Canadian farmers would be well-positioned to rely extensively on domestically produced fertilizer in operating their farms. However, it is important to note that successful crop growth requires a variety of different soil nutrients, some of which are not naturally occurring in soil and must be added through fertilizer application; as such, farmers cannot rely solely on Canadian-produced potash to grow their crops.

Canadian fertilizer production is very heavily concentrated toward potash, with 23 million MT having been produced between July 2020 and June 2021. In contrast, during the same period Canada produced approximately 4.8 million MT of ammonia, 4.5 million MT of urea (a form of nitrogen fertilizer), 1.5 million MT of urea ammonium nitrate (“UAN”), 1.3 million MT of ammonium sulphate, and less than 1 million MT each of ammonium nitrate and other fertilizer products(12).

We can also look to the Fertilizer Shipments Survey conducted by Statistics Canada on behalf of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada for data on what types of fertilizer are shipped by manufacturers, wholesale distributors, and retailers to destinations within Canada to provide context on what types of fertilizers are used in Canadian farming(13). Between July 2020 and June 2021, the most-shipped fertilizer chemicals were urea (3.5 million MT of shipments within Canada reported), urea ammonium nitrate (1.4 million MT); and monoammonium phosphate (“MAP”; 1.5 million MT)(14). In addition to being a widely used fertilizer in Canada, MAP is water-soluble, contains the highest concentration of phosphorus of any common solid fertilizer, and has good storage and handling properties(15).

While Canada’s domestic production of both urea and UAN exceeded the total amount shipped to destinations within the country over that period, the same is not true for MAP(12)(13). In 2020, Brazil, Canada and Australia were the world’s largest importers of MAP, accounting for approximately 32%, 12%, and 7% of global trade value respectively, whereas the top exporters of MAP were Morocco (25% of global trade value), the U.S., (20%), China (19%), and Russia (16%)(6). The specific example of global MAP trade highlights that Canadian farmers do have to rely to some extent on importing certain fertilizer chemicals to generate strong crop yields while ensuring that the soil on their farmland remains in good health. Historically, the majority of Canada’s fertilizer imports have been sourced from the United States, with only a small fraction having been imported from Russia and China(6). With that said, Eastern Canada relies more heavily on Russian imported chemicals than does the rest of the country as there is essentially no local production of nitrogen, phosphorus, or potash in the region(16).

Fertilizer supply contracts are typically put in place by larger, more sophisticated Canadian farmers well in advance to ensure access to supply and allow for long lead times associated with production and shipping, with many of the contracts for 2022 having been established in 2021. That said, the 35% tariff on virtually all Russian imports implemented by the Canadian government in March 2022 went into effect as shipments were already en route to Canada from overseas destinations including Russia(10), which has resulted wholesalers and importers passing the tariff-related costs along to the end purchasers, including farmers(17).

As a result, Canadian farmers are currently in a position where they are reassessing whether they can apply smaller amounts of fertilizer and still achieve strong crop yields, or if alternatives (such as manure) present a viable option to minimize costs. Another unique aspect of Canadian farming is that many producers have some degree of optionality as to what crops they plant. For example, if the fertilizer specifically required to grow corn is not readily available, growers are able to switch to a crop that may need less fertilizer, or to a crop requiring fertilizer that their dealer can reliably source.

While input costs are on the rise, so too are the food commodity prices that drive farm incomes. Canadian farm cash receipts came in at an all-time high in 2021, marking a 9% increase over 2020, due primarily to record commodity prices(18). The strong growth in 2021 farm cash receipts was on the back of an already strong year in 2020, which had seen a 15% increase over the previous year(12). Higher revenue as result of food prices largely keeping pace with increasing input costs has provided some comfort for Canadian farmers with respect to their abilities to tolerate those cost increases over at least the near- to mid-term.

How Does This Affect Bonnefield’s Farmers?

Bonnefield’s farmers, who are progressive, well-established operators and have strong community ties, continue to be agile in their handling of the uncertainty around supply availability and costs. Many of our farmer tenants were very proactive ahead of the 2022 growing season, purchasing fertilizer well ahead of time. In addition, many of our farmers purchase seeds that already contain fertilizer which provides some flexibility as to the timing of fertilizer application should shipping delays occur. This are just some of the many examples of the resilience and business savvy that our farmers have demonstrated over the years.

Our team has heard in recent weeks that farmers’ main concerns aside from input costs remain primarily local for the time being and include domestic supply chain issues such as rail strikes, rising interest rates, and the possibility of unfavourable weather. The continued strength in food commodity prices has led to optimism that 2022 will be another year of strong farm incomes, which are a key driver of Canadian farmland values. Bonnefield offers our farmers long-term leases that are not immediately impacted by rising interest rates, and we act as a supportive partner to our farmers by investing in property improvements that might otherwise be delayed or forgone as result of other unforeseen expenses that strain farmers’ cash positions. As we have since our inception over a decade ago, Bonnefield remains committed to supporting our farmers through all conditions as a true partner in Canadian agriculture.

About Bonnefield Financial

Bonnefield is the foremost provider of land-lease financing for farmers in Canada. Bonnefield is dedicated to preserving farmland for farming, and the firm partners with growth-oriented farmers to provide farmland leasing solutions to help them grow, reduce debt, and finance retirement and succession. The firm’s investors are individuals and institutional investors who are committed to the long term future of Canadian agriculture. www.bonnefield.com

Contributing Authors:

Bhushan Chiniah

Senior Principal

Cameron deGooyer

Prinicpal

Lauren Michell

Senior Principal

Sources:

(1) Green Markets, A Bloomberg Company – Green Markets Weekly North America Fertilizer Price Index (May 2022)

(2) Forbes Magazine – No End In Sight For The COVID-Led Global Supply Chain Disruption (September 3, 2021)

(3) Bloomberg News – U.S. Fertilizer Prices Soar as Storms Roil Industry Hub (September 15, 2021)

(4) Bloomberg News – China’s Curbs on Fertilizer Exports to Worsen Global Price Shock (October 19, 2021); Government of China – Notice of the National Development and Reform Commission and other departments on ensuring the supply and price of domestic chemical fertilizers for a period of time in the future (September 22, 2021)

(5) Reuters News – Russian Ministry Recommends Fertiliser Producers Halt Exports (March 4, 2022)

(6) Observatory of Economic Complexity Data Visualization Tool – Fertilizers (retrieved May 2022; data reported as of 2020, latest available at time of writing)

(7) NASA Earth Observatory – Brazil Battered by Drought (June 17, 2021)

(8) BNN Bloomberg – Major Brazil Soybean Grower to Cut Fertilizer Use Amid Shortage (April 28, 2022)

(9) Financial Post – Nutrien to Boost Potash Production by 1 million Tonnes Amid Worries about Food Security (March 17, 2022)

(10) Canadian dollar equivalent calculated based on the prevailing CAD/USD spot foreign exchange rate of 1.2808 as at December 31, 2020 per the Bank of Canada

(11) Government of Canada; Natural Resources Canada – Potash Facts (February 3, 2022)

(12) Statistics Canada – Table 32-10-0037-01, Canadian Fertilizer Production by Product Type and Fertilizer Year, Cumulative Data (x 1,000); data for the period between July 2020 and June 2021.

(13) Statistics Canada – Surveys and Statistical Programs, Fertilizer Shipments Survey; Detailed Information for the Second Quarter of the Fertilizer Year 2021/2022

(14) Statistics Canada – Table 32-10-0038-01, Fertilizer Shipments to Canadian Agriculture and Export Markets by Product Type and Fertilizer Year, Cumulative Data (x 1,000); data for the period between July 2020 and June 2021.

(15) The Mosaic Company – Monoammonium Phosphate (retrieved May 2022)

(16) Toronto Star – Island Farmers Told Ukraine War Threatens Canada’s Food Supply Chain (April 6, 2022)

(17) Global News – Critics Say Federal Support for Canadian Farmers puts “Water on a Grease Fire” (May 6, 2022)

(18) Statistics Canada – Table 32-10-0045-01, Farm Cash Receipts, annual (x 1,000). Data noted reflects the year-over-year increase in Total Crop Receipts.

This document is for information purposes only and does not constitute an offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities in any jurisdiction in which an offer or solicitation is not authorized. Any such offer is made only pursuant to relevant offering documents and subscription agreements. Bonnefield funds (the “Funds”) are currently only open to investors who meet certain eligibility requirements. The Funds will not be approved or disapproved by any securities regulatory authority. Prospective investors should rely solely on the Funds’ offering documents which outline the risk factors in making a decision to invest. No representations or warranties of any kind are intended or should be inferred with respect to the economic return or the tax consequences from an investment in the Funds. The Funds are intended for sophisticated investors who can accept the risks associated with such an investment including a substantial or complete loss of their investment.